Jim Monahan

Revolution was in the Air

By Rebecca Sloane

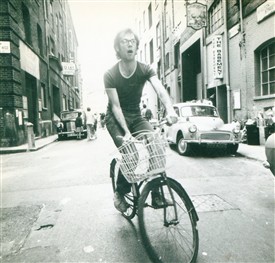

Jim Monahan cycling c1974

Covent Garden Community Association

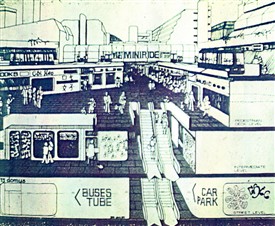

Proposed plans for Covent Garden

Covent Garden Community Association

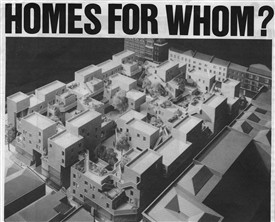

Model of proposed development

Covent Garden Community Association

The days after the market moved from Covent Garden to Nine Elms

Penny Saunders

Demonstrating against the proposed plans outside St Pauls

Covent Garden Community Association

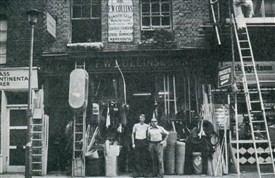

Fred Collins outside his shop

Covent Garden Community Association

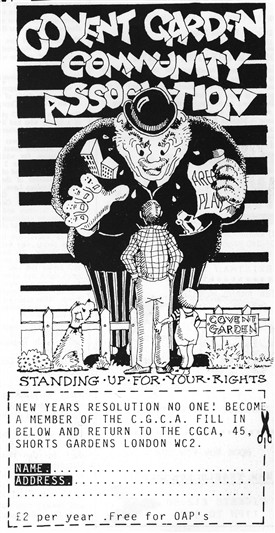

One of the many campaign illustrations by Jamie Monahan

Jim Monahan

Demonstration to save Covent Garden c1980

Covent Garden Community Association

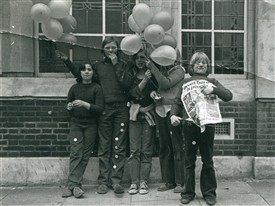

Children demonstrating, 1972

Covent Garden Community Association

On May 10th, I had the pleasure of interviewing Jim Monahan, an architect and resident of Covent Garden. Speaking eruditely and persuasively about the values that underpin his activism today, it was easy to imagine Jim, the young campaigner and activist as he was in the ‘70s and ‘80s. He believes now, as he believed then, in the power of individuals to work together for what they think is right. He thinks that ‘[when] the land is owned by the public…the public should determine what should happen [to it]’.

Jim helped to set up the Covent Garden Community Association 1971. At the time, he was a student architect at the Architectural Association in Bedford Square and devoted himself nearly full time to fighting the proposals of the Greater London Council, Camden and Westminster. Although Jim speaks modestly about his personal involvement, it is plain that he was instrumental in organising the campaign to save Covent Garden from ‘the last gasp of the modern movement’s large-scale redevelopment plans’. He remembered the famous march to Trafalgar Square in 1973, the occupation of buildings like Centre Point, the building of community gardens and the formulation of Acts of Parliament as examples of the activism of which he is justifiably proud. Many times he squatted in Covent Garden buildings to protect them from demolition (as well as to have a place to live!). Jim reflected that the authorities had a hard time predicting, and therefore countering the activists, because, in a way, their actions were so ‘anarchic’. One particularly effective tactic to raise the awareness of landlords and tenants was to put posters on buildings announcing the date in which they would be demolished. Jim’s special expertise as an architect enabled him to decipher complex redevelopment plans; with others he helped to identify which buildings were being targeted. Campaigners were also aided by the fact that Covent Garden was in the heart of London and near to the press industry (which helped to publicise issues) in Long Acre and Fleet Street. Many students, including some from LSE, from the Architectural Association and Bartlett School of Architecture (UCL), became involved in the campaign. Jim recalls that it was a heady time when ‘revolution was in the air’.

Jim fondly remembers, in addition to Austen Williams and John Toomey, one local character, Fred Collins, a stalwart activist who helped to claim land for the building of community gardens. Fred had a sign on his shop window Sole Inventor of Elastic Glue, which he claimed that his father had invented. Fred said that the glue was also a good cure for coughs and colds! Fred ‘came alive because of being surrounded by young people and… he was a great campaigner… One night we were digging up pavements and putting trees in and … putting pick axes in the ground and [were] just missing the electric cables…[it was] complete madness!’.

Although not all of the aims of campaigners were achieved, Jim is proud of the fact the large-scale redevelopment of the area was stopped. Had the redevelopment gone through, 50 acres of the Covent Garden would have been flattened. The campaign’s success in substantially increasing the residential population contributed to the ‘saving’ of the two primary schools. Additionally he is proud of the campaign’s achievement in building community centres, the abandonment of the scheme to widen Charing Cross road, the redevelopment of Cambridge Circus and in stopping the destruction of five or six theatres that were scheduled to be demolished. Jim was also involved in the ten year campaign concerning the redevelopment of the Royal Opera House, in particular the retention of eight bays of the listed Floral Hall, abandonment of a 300 capacity underground car park on the site and 250,000sq. feet of speculative offices. Jim thinks that, for him personally, the campaign provided a huge number of friendships which has given him ‘a context for [his] life’. Laughing as he sums up his personal involvement he says: ‘I know my way around agitprop and can still be quite awkward…’

Despite all the achievements of the ‘70s and ‘80s campaigns, Jim also remembers the disappointments. He reflects that the activists were ultimately unable to prevent the growth of the ‘candy floss economy that has taken over’. He is angry that current government policies, which began in the 80’s and 90’s, arbitrarily consider commercial success and land value as their highest priority. Many of the interesting activities of the area that had to do with manufacturing and with theatres were pushed out as a result of government policies, leaving the current economy of the area dependent on advertising, tourism and entertainment. The departure of the Flower Market was tragic; Jim asserts that forcing it out was a very unimaginative decision, as it didn’t significantly contribute to congestion. He considers that the closure of the fruit and vegetable market was sadly inevitable with the growth of super markets which purchase fruit and vegetables directly from growers and bypass wholesale markets. He describes the last days of the market very poignantly. Seeing all the empty barrows lined up, all the way down Neal Street from John Sullivan’s barrow makers’ workshop was for him, a ‘manifestation of death’. Their visual appearance made him think of ‘coffins’.

At the end of the interview I asked Jim if there were anything further he’d like to add. He would like to deliver a clear message to people, especially children, that they shouldn’t be fearful if they want to change their communities. He worries that London, which historically has been a city in which rich and poor live side by side, is becoming more segregated. He hopes that people will ask the question: “Will this development be beneficial for children?” Jim thinks that planners should give this question highest priority and this simple criteria be incorporated into planning law. Ultimately then, the resulting development will improve everyone’s life.

This interview was conducted as part of the Lottery Heritage Fund project, ‘Gentleman We’ve Had Enough: The Story of the Battle to Save Covent Garden’. On Friday 10th May 2013, King’s College London students, supported by Westminster Archives, the Covent Garden Community Association, and the Centre for Life-Writing Research at King’s College London, interviewed Covent Garden residents about their memories of the area. Students’ accounts of their interviews have been added to this Covent Garden Memories website. For more information see: www.kcl.ac.uk/artshums/ahri/centres/lifewriting/gentlemen.aspx.