Bernard O'Connor

'Really lovely days'

An interview conducted by Anne Chapman

Covent Garden Market

Penny Saunders

Coronation party in Betterton Street around the time Bernard moved to Covent Garden, 1953

Covent Garden Community Association

Local Covent Garden community, c1950s

Covent Garden Community Association

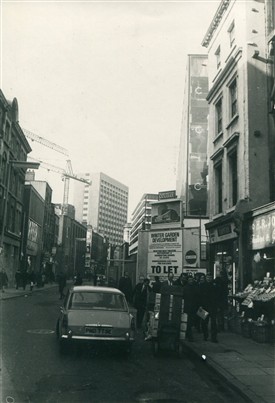

Drury Lane, 1971

Covent Garden Community Association

Two things stood out to me when | interviewed Bernard O’Connor in the Seven Dials Club on a Friday evening in May 2013. The first was his cheerful outlook; with the exception of his thoughts on the practices of some unions, he had nothing negative to say about both his life and Covent Garden. The second was how important a sense of community is.

Bernard arrived in Covent Garden in 1953 from Carshalton in Surrey. He began by working as a telegram boy in Leicester Square, cycling round on his push bike, delivering telegrams. His vivid description of the smog brought that time to life for me: You couldn’t see your hand in front of you and it was so dangerous that the bus conductor would walk along with a flare in his hand to light up the kerbs so that the driver could see where he was going. In the early 1950s there wasn't a lot of traffic on the roads, so there weren't many accidents. Yet if you had chest problems the smog could kill you. It could go up extremely high and then above that would be clear. ‘So you could climb up a building and you could see it was clear’. Gradually, in the years following the Clean Air Act of 1956, it became better.

After being a telegram boy and spending three years in the army, Bernard worked for a soft furnishings company and this is where he met Kath, his wife, who was born in Drury Lane. They were both invited to a wedding, and, as Kath didn’t know where to go, Bernard offered to give her a lift on his motor scooter. He described her having to ride side-saddle in her pencil skirt like Audrey Hepburn. They married in 1962 and, at least until the market closed, they were surrounded by her family. He felt that he was made welcome straight away and, when it came time to move to a bigger flat, the family helped them out moving their furniture with a barrow from the market.

They got married in the church on Maiden Lane and had their reception in a pub on the corner. People had a lot to drink and some of them got in trouble because they were ‘drunk and disorderly’. Kath’s aunts were flower sellers in the market, known to everybody, so they went to Bow St police station and convinced the police to let them all out again; nobody was charged. ‘It was a really lovely day.’

The way residents behaved towards each other in the 1960s goes some way to explaining the ‘village atmosphere’ about which Bernard talked. There were no locks on the doors in the first flat he and Kath lived in; you had to try and lock the door with the sort of padlock you might have on a garden shed. Kath would unlock the door after she got up. On a Sunday morning, the first day he and Kath had been in their flat after their honeymoon, they were sitting having breakfast and chatting when somebody came along, knocked on the door, opened it, and just walked in. It was a cousin of Kath’s come to see if Bernard wanted to go to the pub to play darts. It was a time when people would be comfortable just walking into their neighbours’ flats. ‘It was really lovely days’.

Bernard and Kath’s first flat was nothing like what we would expect today: two rooms, no bathroom or even running water, just a cold water tap shared by three flats and a washroom you could use for bathing and washing and drying clothes. This sounds very difficult, as indeed Bernard said it was, especially when you consider that they had the terry toweling nappies of twins to deal with. Yet Bernard talked of living there with enormous affection. ‘I remember getting up for work in the morning ... and I remember with the tap on and soap and then washing my face in the sink and the girl next door to us, Mary, she came out with one of her children and she'd be in her nightdress and she'd come out, “Morning Bern”. I said “Good morning Mary” looking under my arm and could see she was in her nightdress ... nothing nasty about it. It was just so free and easy. Everybody was so free and easy with everybody. We knew everybody, everybody knew us and it was just grand.’

Bernard described to me what it was like walking home from the pub on a weekend evening at the time when the market was still there. ‘The area was totally deserted, absolutely deserted. You wouldn't see a soul. The Strand was chock-a-block with people, and Kingsway, and St Martin's Lane with theatres. There were loads and loads of people around. But here was totally empty.‘ Stall holders would simply lock everything up and would put railings around all the bags. You would walk along and see rats running about because there was nobody there.

It’s perhaps unsurprising, then, that Bernard didn’t want things to change and was part of the protests in the 1970s. He remembers that, ‘we walked about, but we weren't sure what we were protesting for. We were more or less protesting for the status quo, for it to remain the same. Although in our hearts we knew that this couldn't happen.’ He described his brothers-in-law, like many others, moving out of the area once the market closed, and so in fact change seemed inevitable; ‘it had to change’.

‘After all's said and done, it's money that decides, really, ... it's people who've got the dough that actually make the decisions on these things’. Bernard didn’t complain about what has become of Covent Garden, however. He still has a sense of community. ‘We get lots of immigrants there now ... they're all nice people. I get on very well with the fella in the next block who's Iraqi ... They're a really lovely family. ... It's just not your cousins anymore or your in-laws’. Bernard has been passing his yearly cab driver medical ever since he turned 65 and you might still be driven by him, should you take a taxi in the morning. In the afternoons, he often takes advantage of the opportunities close by, visiting The British Museum, The National Gallery and Tate Britain, amongst others. He also likes going to some of the pubs where the landlords still have connections to early days and he involves himself in some of the charity work that goes on also. He has had the opportunity to move back to Surrey but I wasn’t at all surprised that he had never wanted to. ‘I love living here’.

This interview was conducted as part of the Lottery Heritage Fund project, 'Gentlemen We've Had Enough: the Story of the Battle to Save Covent Garden'. On 10th May 2013 King's College London students, supported by Westminster Archives, the Covent Garden Community Association, and the Centre for Life-Writing Research at King's College London, interviewed Covent Garden residents about their memories of the area. Students' accounts of their interviews have been added to this Covent Garden Memories website. For more information please see: http://www.kcl.ac.uk/artshums/ahri/centres/lifewriting/gentlemen.aspx.