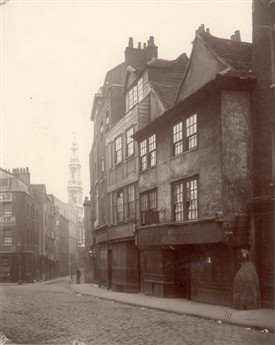

Victorian Improvement & Destruction

Houses survived the great fire of 1666 but didn't survive the improvements of Aldwych in1901 Alfred Henry Bool 1876

Westminster City Archives

Impoverished street scene in Dudley Street north end of what is Mercer Street today in Seven Dials. Gustave Dor 1872

Westminster City Archives

Sandringham Buildings 2013

Covent Garden Community Assocation

Victorian plaque on Sandringham Buildings

Covent Garden Community Assocation

Clearance for Aldwych and Kingsway Credit

Covent Garden Community Assocation

Dickens wrote of the dire poverty in Drury Lane and Seven Dials in the 1830s, and the cholera epidemic of 1849 hit the area hard. When Wild Court, off Drury Lane, was taken over by Lord Shaftsbury's ‘Society for Improving the Condition of the Working Classes’ in 1854, over a thousand people were found living in 13 ten-room houses with virtually no sanitation.

By 1860, appalling living conditions prompted the Bedford Estate to act. But ‘improvement’ yet again meant evicting tenants, and refurbishing or pulling down decayed houses in order to rebuild property that would attract higher rents from a better class of person. Other landowners followed suit for the rest of the 18th and 19th centuries, but with patchy results. The cycle of subletting usually returned - perhaps because people have never wanted to be forced away from their communities, and some will always find a way to stay.

In the 1880s, 4,000 people were relocated when Shaftesbury Avenueand Charing Cross Roadwere cut through the north and west of Covent Garden for slum clearance and (non-motorised) traffic improvement. By then, legislation required alternative accommodation to be provided for the ‘labouring-class’. After negotiation with the developers, just half the people were re-housed. Many moved into new blocks near what is now Cambridge Circus, with names such as Sandringham Buildings that we recognise today. But much of the 18th century fabric of the area was destroyed.

Fortunately, not all social reforms were so destructive of communities. As part of slum clearance ordered by the then Metropolitan Board of Works, Peabody Trust built large blocks of dwellings on Wild Street and Bedfordbury in 1882 to rehouse those displaced on the same spots. They built a storey higher than usual because of the sheer numbers of people in need. Peabody pioneered ‘luxury’ social housing at the time, with outside space for recreation, and separate laundry facilities - but no running water in the flats.

In 1901-05, acres of slums were cleared on the east side of Covent Garden to make way for Kingsway. 600 historic buildings, including some from Tudor times, were flattened - again in the name of traffic flow and improved conditions. A tram subway was installed, and more than 3,000 were people were relocated. Most were moved to Millbank, but land for some more local re-housing was bought from the Bedford estate in 1900 by the London County Council. They built blocks such as Stirling, Siddons, Sheridan, Beaumont and Fletcher Buildings near Drury Lane. Some of these council flats were to play a key role in the 1970s.