George Bernard Shaw

Life and works

By Ashley DeMattio

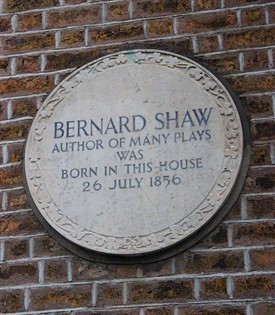

Shaw was born at 33 Synge Street, Portobello, Dublin.

George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) was a self-taught playwright, literary and music critic, novelist and social commentator. He grew up in Ireland and moved to Britain during a time when social classes were rigidly constructed and opposed. In a prolific career he investigated themes of politics and society, including them within his plays, novels and public speeches.

Shaw was an individual who knew what he wanted: socialist reform. Demanding social change, he became a well-known public speaker in late Victorian British society, communicating his views vociferously in the public sphere.

Shaw also gave life to the British Theatre in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, his views expressed through his creative works of art. Today, Shaw is remembered for the quality of his writing and commentary on his times.

“Devil of a childhood”

George Bernard Shaw’s described his early years as “a devil of a childhood". He was born in Dublin on 26 July 1856. His father, George Carr Shaw, was a civil clerk turned wholesale food (corn) merchant. He was also an alcoholic, which he denied. This denial shaped not only young George's life, but also affected his mother, Lucinda Elizabeth Gurly Shaw.

Lucinda was from a well-to-do family, raised to be a lady and promised her aunt's fortune.That all changed once she met George Carr Shaw. Lucinda’s family soon found out that Carr Shaw was a drunk. When she still decided to marry him, her aunt cut her off from the fortune.

Shaw’s mother was very strong-willed and calm through the time of her marriage. But she had little to do with her children and they were left to be taken care of by maids. Lucinda only knew one way to escape the way of life she had chosen and that was through music.

Lucinda was a singer who studied under the conductor George Vandaleur Lee. His voice training first captivated her and then became something much closer. Vandaleur Lee was a constant presence in the bohemian Shaw household, imbuing young George with a strong interest in music from an early age. Lucinda embarked upon an affair with Lee and left her husband. Both left Ireland for London in 1873 to further their singing and teaching careers. Shaw was 16 years of age when she departed. He would follow her to London in 1876.

Shaw’s education

As a young boy Bernard Shaw briefly attended Wesley College in Dublin. From a Protestant background, Shaw found himself surrounded by Catholic boys from tradesmens' homes. He hated the school and reacted badly to its teaching methods. He referred to the curriculum as “Latin is still the be-all and end-all of education”. Needless to say, Shaw did not excel there. He subsequently attended the Dublin Central Model School and finally the Dublin English Scientific and Commercial Day School, which he found more conducive. Here, Shaw found a great love for Shakespeare and his understanding of vocabulary astonished his teachers. Mostly self-taught, Shaw showed his intellectual skills through his writings later in life.

Career opportunities

Shaw had various jobs throughout his life, the first of which was for an estate agent in Dublin. He did not particularly like this, but he knew that he had to have an income to contribute to the household expenses. In 1876, Shaw wrote six novels, all considered unsuitable for publishing. When he moved to London his mother supported him and to gain extra money he 'ghost-wrote' musical articles for Lee. This gave him a small income. For a short time he was also employed by the Edison Telephone Company. During this period he spent much time in the Reading Room of the British Museum, improving his literary education. He attended socialist meetings in the evenings, where he embraced atheism, social liberalism and, from 1881, vegetarianism.

Shaw then landed a position as a freelance critic for the liberal daily The Pall Mall Gazette from 1885-1888. Even though Shaw was not successful with his first novels, he became very well known for his journalism. Whilst at the Pall Mall Gazette, Shaw was introduced to its editor WT Stead. Stead revolutionized London journalism through his racy topics and writing styles. Their relationship is later understood through one of Shaw’s plays. Shaw's talents were recognised by fellow-critic William Archer, particularly his critiques of paintings and art. Archer asked George if he would help him publish criticisms, and later offered him a full-time writing position. These experiences helped Shaw to realise his full potential and gain a foothold in London literary society.

The influence of socialism

At various points during his life Shaw claimed he was influenced by historical figures such as Napoleon, Mussolini and Stalin. But the greatest influence on Shaw, by far, was communist thinker Karl Marx. Shaw was encouraged by H. H. Hyndman, the leader of the left-wing Social Democratic Federation (SDF), to read Marx's Das Kapital. The book proved to be pivotal in Shaw's evolving personal political philosophy. Das Kapital convinced him that socialism and reform could change society for the better. He believed that all major problems would be solved if Socialism was implemented. He became a true Marxist believer, fascinated by the German author's claims that the interplay of economics and politics were prime drivers of social progress.

Fabian Society

Shaw was drawn to the new left-of-centre Fabian Society (founded 1883), after reading its book 'Why are the Many Poor?' . He made his first appearance at a Fabian meeting on 16 May 1884 and became a member in September the same year. He was heavily involved in the Society and was elected to the executive committee soon after joining. He was introduced to a variety of people within the Society, among them its founders Sidney and Beatrice Webb. The Webbs epitomised Fabian Society ideals and Shaw and the couple became very close. Shaw was subsequently involved in the so-called Bloody Sunday demonstration in Trafalgar Square on 13 November 1887. This demonstration - incited by the radical left-wing Social Democratic Federation (1884) of which Shaw was also a member - turned violent and was broken up by the police, resulting in many injuries and several fatalities.

Women in Shaw’s Life

As a self-professed socialist Shaw believed that women should have exactly the same rights as men. Shaw felt that women had a critical role to play in human society, although he also revealed something when he suggested that “they were not important to my daily life, but were important to my art". Bernard Shaw thought of all people as having a purpose in life. Yet everyone was to do what was not best for them, but best for society as a whole. He viewed women in this same respect and had a very socialist view on relationships. He did not believe in traditional marital relationships. He did fall in love with Ellen Terry, an actress in several of his plays, not as a woman (he claimed) but as an actress.

Shaw eventually married Charlotte Paine-Townsend in 1898. The marriage was against all he stood for, but after an accident in 1897 he needed someone to take care of him. He said “I thought I was dead, for it would not heal, and Charlotte had me at her mercy. I should never have married if I had thought I should get well". The marriage was never consummated. Charlotte knew that even though she was in love with him, he would never feel the same for her. Shaw had various affairs with actresses in his plays, claiming to only love them for their roles on stage. Shaw perceived women thus: “Unless woman repudiates her womanliness, her duty to her husband, to her children, to society, to the law, and to everyone but herself, she cannot emancipate herself.” Shaw’s representation of women is clearly seen in his most famous play, Pygmalion.

Pygmalion

Shaw wrote Pygmalion in 1912. It won him a Nobel Peace Prize in Literature in 1925. Pygmalion was written with the Suffragette movement in full flow and Shaw was partly inspired by memories of his time as a freelancer at The Pall Mall Gazette. In July 1885 the Gazette's editor WT Stead had published three lurid articles on 'White Slavery': The Maiden Tribute of Modern London. At a time of strict - if hypocritical - Victorian morality Stead had caused outrage by publishing stories of prostitutes and young girls sold on the streets to well-heeled members of British society. Stead interviewed prostitutes, madams, clients, policemen and others on the threat to young, female virgins. Virginity, he asserted, was a sanctity which a “woman ought to value more than life”. One of the three Maiden Tribute articles that caught Shaw's attention in particular was: “A Girl of Thirteen Bought for 5 Pounds”. This article was very detailed and chilling in its authenticity. Stead had purchased a 13 year old girl, Eliza Armstrong, from her mother in a well-planned press entrapment operation. She was not mistreated or abused, but passed to the Salvation Army in France.

Stead's actions gave him a major press scoop and allowed him to show just how easy it was to purchase young girls such as Eliza. Stead’s purpose was to promote change and to inform society what was happening around them. At the time Shaw did not believe in such journalism tactics and criticised Stead.

Stead was jailed for three months for his radical action but he felt he had proved his point. This and other social reform movements of the 1890’s and 1900’s inspired Shaw to write Pygmalion. In part, the theatre served as his tool to promote social change. The main characters in the play, Eliza Doolittle and Henry Higgins, represent reform and conservatism. Professor Higgins gives Eliza the opportunity to change her reprobate cockney ways, and become a proper lady.

Throughout, it is not known what Higgins actual intentions are for the young girl. Shaw uses Eliza’s father as a pivotal device. Significantly, when Higgins pays Mr Doolittle for Eliza, he says that: “She is at an age of interest”. Pygmalion repeatedly exposes the dual nature of relationships between social reformers and young, unmarried women. This statement reveals the mindset of the Victorian and Edwardian time period and the clashing British social classes. Shaw hoped that unveiling such (impure) thoughts in a comedic and theatrical setting might revolutionize popular perceptions of society as it was then constructed.

Throughout the play there are various links to the Maiden Tribute, and Shaw also included a twist at the end of his play. He was very specific that he did not want Eliza to go back to Higgins. Shaw wanted to show her character as a strong independent figure. This is shown at the end of the play when Eliza turns down Higgins' marriage proposal. She then threatens him that she will leave by saying, “I will marry Freddy, I will, as soon as I am able to support him”. Shaw’s play ends with Eliza leaving and not returning to Higgins’ home. She has proved that she too has limited options, and can only indulge in those options as an independent individual. Shaw clearly allowed his play to be taken in many different directions and uses various scenes to make political and social points.

Later writings

George Bernard Shaw - styling himself 'GBS' - wrote a series of plays after Pygmalion. He continued to illustrate social and political themes within his plays which he felt audiences might relate to. He became an influential voice within the British theatre establishment. His lean, white-bearded features became a fixture of left-leaning literary salons across London and beyond. Unsurprisingly, he strongly opposed both world wars, expressing his views forcefully in the British and international press.

He also wrote several books, including Common Sense about the War and articles for the left wing periodical The New Statesman. Notoriously, Shaw was among many of his political persuasion to praise Joseph Stalin after visiting the Soviet Union in 1931. Shaw’s political views inclined toward the utopian concept of Soviet society and he was criticised for ignoring the reality. When he visited the United States, in the 1930s, his self-aggrandising, contrarian personality was strikingly evident in newsreel footage.

Shaw’s legacy

Shaw’s last play was Why She Would Not, which he finished in July 1950. A couple of months later, on 19 September 1950, Shaw suffered a fall and was bedridden. He developed kidney failure and died on 2 November 1950. His legacy lives on today and is celebrated within the theatre, globally. He impressed many with his use of art, theatre, politics, and social reform. In 2012, as the centenary of his play Pygmalion is celebrated, George Bernard Shaw is also remembered for his many enduring works within the theatre, his numerous publications, and his ideas as a social and political thinker.