Kathy Pimlott

The Heart of Covent Garden

An interview conducted by Hope Wolf

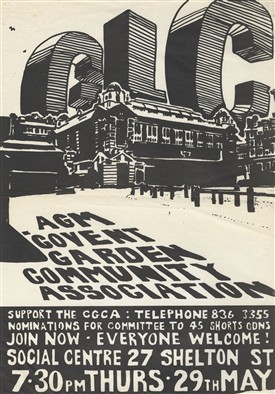

Covent Garden Community Association AGM poster

Covent Garden Community Association

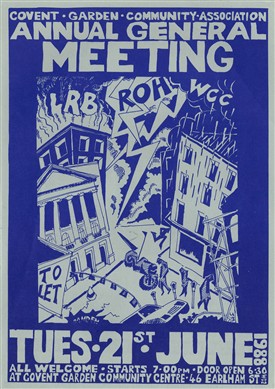

Covent Garden Community Association AGM poster

Covent Garden Community Association

1976 May Fayre in Covent Garden

Covent Garden Community Association

'I just can't imagine living anywhere else,' says Kathy Pimlott, Covent Garden resident since 1976. She brought up her children in the area, and also worked locally. Formerly a co-ordinator of the Covent Garden Community Association, she now works for the community-led Seven Dials Trust.

A little blooming

By the time Kathy and her husband had moved into Covent Garden, the old market had already been relocated. The area then was quite different from the bustling place it is now: ‘everything was closed up, and it was quite deserted.’ Kathy was living in short-life housing in Bedfordbury at the time, just two minutes away from Trafalgar Square. Between Bedfordbury and Endell Street (‘where the swimming pool is, and where the baths were’) the streets were then so empty that ‘you could walk down the middle of the road’.

It would be inaccurate to portray Covent Garden at this point in its history as a sad place. Kathy remembers ‘beautifully desolate’ Sundays, and enjoyed a kind of ‘freedom’: ‘I liked having the space’, she says; ‘ You weren’t being overlooked because there was nobody there.’ The absence of the market, and the relatively cheap property prices, also presented opportunities for new residents and traders. ‘Very small enterprises’, ‘arts and crafts’ and ‘alternative’ organisations moved into the area, next to the remaining shops serving the residents: butchers, greengrocers, and the fish stall in the old Jubilee market.

Yet this ‘little blooming’ was short-lived. The new market opened (in place of the old one), and that quiet, spacious version of Covent Garden, with its independent shops and stalls, ‘crashed and burned’ as ‘the property and rental values rocketed’. Kathy speaks vividly of the opening of the new market in 1980, ‘to which we weren’t invited, standing at what was the Opera House end with my daughter in a pushchair, shouting at the top of my voice about the housing; about who Covent Garden really belonged to.’

‘No chains’

Although by the time Kathy moved to Covent Garden ‘the big battle to save was over’ (the campaign of 1971), the Covent Garden Community Association continued to work to ensure development plans aligned with the needs of residents. A year after the new market opened, Kathy was working for the Association. It was a diverse group, mixed in age and background: both ‘local, genuinely local, people’ and ‘young and not so young radical incomers’. She reflects that diversity was essential to the successful working of the group: ‘You do need that radical input, confidence and bloody mindedness. But you do also need the genuine commitment and involvement of the people to whom Covent Garden really belongs.’

Lest Covent Garden become another ‘Bond Street or Oxford Street’, the Covent Garden Community Association sought to prevent the growth of chain stores in the area: ‘No chains, no chains. That was the whole thing: there wouldn’t be chains.’ However, there was a sense in which Kathy felt that they were struggling against the inevitable. ‘What happened next was what was always going to happen’, she says: Covent Garden ‘was going to be made money of, in some way’. The irony was that the more work that was put into preserving Covent Garden as an historic and social centre, the more attractive it became to corporate interests; in that sense, says Kathy, ‘it was a victim of its own success.’

‘What was going to happen to this property?’

It was not only the fabric of the area and independent trading that the Covent Garden Community Association sought to protect, but also the housing stock. Many residents, ‘lots of old girls’, many of whom had worked in the market or at the print works, were living in ‘very substandard accommodation, very old, very rundown, poorly maintained social housing.’ The three blocks of Martlett Court had ‘toilets, but no bathrooms for ages’; ‘there were flights of stone stairs but no lifts’; they were ‘tiny, tiny, tiny, tiny flats’ (although they are now selling for ‘close on half a million’). The Association ‘was very keen that people who had a very real connection to the area be given priority in the allocation of new or refurbished residential properties’. As a result, some remained where they were, some moved to the newly built Odhams Walk and Dudley Court, and some to the various smaller GLC (Greater London Council) new-build. The Association looked after people with housing need, and also worked to help families stay together: ‘as families grew up, where would the next generation live?’

Kathy remembers the difficulties the Association faced following the abolition of the GLC. The GLC owned a great deal of property in the area (they had ‘bought up huge swathes of Covent Garden because they were going to knock it down’). The question, following its abolition, was ‘what was going to happen to this property?’ Because of the Right to Buy scheme, introduced under Margaret Thatcher’s Government, some of the former GLC and local authority owned residential properties were bought by tenants, who then sold them on for a substantial profit. One legacy of this is the mixed character of the ex-GLC blocks: ‘half social housing, and the other half are owned by private leaseholders, who often rent them out, at expensive rents, on short contracts.' Kathy’s block, then, comprises ‘all these social tenants, who are often extremely grumpy with the short-term tenants who have no sense of living in a community.’ ‘It’s very odd’, she says, ‘the flat above mine, which was originally a one bedroom, was on the market for over a million pounds. My neighbours on both sides and I, we’ve lived in these flats for nearly thirty years. We’re slap bang in the middle of London, in a prime property location, but it’s just home to us.’

‘Trying to stop the erosion’

As co-ordinator of the Covent Garden Community Association, part of Kathy’s role was to listen to the needs of residents. The Association operated ‘an open door office’, and people would drop by to discuss their needs: ‘saying, you know, I've got four children, and I live in a two bedroom flat and the electrics don't work.’ Some would visit Kathy to gossip, others to discuss legal and domestic issues. Kathy felt it was her obligation, if she did not have the knowledge to help, to ‘find someone who could actually give that advice’; ‘we did a lot of writing on people’s behalves’, she says.

The attempts of the Association to ensure that, in any redevelopment plans, residents’ interests were protected should not, Kathy explains, necessarily be described as ‘a battle’; it was, rather, ‘like trying to stop the erosion of what the whole point had been in doing it [i.e. campaigning] in the first place.’ The campaign had many aspects: there was the campaign against the development of the Opera House, the campaign to save the Jubilee Hall and market, as well as smaller but important issues like ‘zebra crossings, community provision and the protection of the wonderful buildings’.

Throughout these campaigns, the Association sought to strike a balance between a ‘perfectly natural desire’ for safety (‘everyone wants to be in a safe environment, nobody wants to be frightened in the streets at night, or to think they’re going to be broken into’), and a competing wish to ‘retain the individuality and texture of the area’, to keep it ‘multi-layered’ and ‘multi-textured’. There was a danger that Covent Garden could turn into a ‘Disney Land’, and while some members of the Association ‘thought it unlikely you could actually stop the homogenisation and commercialisation of Covent Garden’, it was nonetheless important to act against the odds: ‘Somebody’s got to say, “no, it shouldn’t be like this”.’

The heart of the city and the heart of Covent Garden

Towards the end of the interview, I asked Kathy if she thought the Covent Garden Community Association had a consistent ‘enemy’. She answered, ‘if you want a broad brush, the enemy is always going to be capitalist interest; the enemy is always financial interest, always. It just manifests itself in different ways.’ The opposing power was clearer in the early 1970s’ campaigns: ‘the enemy was the GLC – because they had the power. They owned it. They made the rules. That was definitely little against big.’ However, this has shifted over time: ‘the battles get smaller’; now residents aren’t defending ‘issues of principle’ in such a straightforward way. Before the issues were ‘manifest in the sense that they were there in bricks and mortar’; the Association formerly asked: ‘who owns this, who actually owns this?' and ‘who has the right to say what should happen to it?’ Now, says Kathy, ‘you’re battling against individual things, like who’s put out six chairs when they should only put out two, who’s got a late-night license, and drug abuse on the streets.’

‘But it’s a lovely place to live’, Kathy concludes. Some of the community activities no longer take place: the community theatre, the May Fair, the festival in September, Bonfire Night and the Easter Parade. However, public spaces like the Phoenix Garden (Kathy’s husband was the community gardener on the six original community gardens in the area in the 1980s) are ‘thriving’. She mentions the two primary schools, and the two community centres. And this is ‘unusual in the heart of the city, in such a vastly valuable piece of real estate.’ For Kathy, the ‘heart’ of Covent Garden, the ‘key’ to preserving its vitality, the aspect that keeps the ‘balance’ and ‘mix’ in the area, is having ‘enough social housing and private housing that has not been given over to short-term letting’. Despite all developments, there is, she says, still a ‘community’ in Covent Garden, ‘There are still ordinary people carrying out their ordinary lives. There are still people for whom this is home. There are still people for whom this has been home for two or three generations, and I think as long as you can keep that going, then it will retain its heart.’

This page was added by

Hope Wolf on 19/06/2013.